Anki (St. Olaf Latin 112)

Anki is a program that helps you memorize and remember information. It is much more efficient than traditional study methods because it shows you information only right before you're about to forget it. If you choose to use it, it will likely be the most powerful learning tool you will have (aside from other people, books, and the Internet).

Anki Decks

If you haven't used Anki before, skip to the next section and read about why you want to use it first. There are instructions at the bottom of the page for installing Anki.

To import one of these files into Anki, click the link and download it, then double-click on the file. If it's not open already, Anki will open and confirm that the cards imported correctly into your collection. If you run into any problems with downloading or importing, notice I've uploaded or linked the wrong thing, or find any mistakes in the decks, please let me know! With a collection this size, there are likely to be some errors.

These cards are pulled directly from Wheelock's Latin lists and include most of the derivatives and other information (but not quite all; I removed some duplicates and in-my-opinion unuseful information).

A little bit of explanation about the "Mnemonic" field. If you notice you're having difficulty remembering a card, you can make up some sort of memory device, then press 'e' for edit while you're studying and type a description in the field, and thereafter it will show in gray on the answer side of cards to give you a reminder of how you were supposed to remember it. It's empty initially on most of the chapter 10+ vocab, except where I filled in a note the book had about the word; if you download some of the older ones, you'll see that I've filled a few of them in with my own mnemonics, but they won't be very helpful for you, so feel free to remove them (and add your own!).

Latin 112

(If your browser displays a page of gibberish instead of downloading the file, right-click the link and choose Save Link As.)

Chapters 25-40

Chapter 40

Chapter 39

Chapter 38

Chapter 37

Chapter 36

Chapter 35

Chapter 34

Chapter 33

Chapter 32

Chapter 31

Chapter 30

Chapter 29

Chapter 28

Chapter 27

Chapter 26

Chapter 25

Latin 111

Chapters 1-24 (warning: lots of cards!)

Chapter 24

Chapter 23

Chapter 22

Chapter 21

Chapter 20

Chapter 19

Chapter 18

Chapter 17

Chapter 16

Chapter 15

Chapter 14

Chapter 13

Chapter 12

Chapter 11

Chapter 10

Chapter 9

Chapter 8

Chapter 7

Chapter 6

Chapter 5

Chapter 4

Chapter 3

Chapter 2

Chapter 1

Note: I don't know what kind of copyright vocabulary lists are under. Whatever the answer, I don't claim to hold copyright on these lists. If you think you do and you have a problem with my usage of them, please send me an email (see the very bottom of the page for contact link).

An Overview of the Spaced Repetition Method

You don't absolutely have to read this to use Anki, but it'll give you some useful background on the theory behind the software. You're at college to learn things, after all, so it makes some sense to learn something about learning before you try to do it.

The forgetting curve is a mathematical projection of when we're likely to forget information we've learned. Generally speaking, if we do not review what we've learned, we forget much of it quickly (see the dotted blue curve). However, as the Reminder curves show, it's not difficult to keep it for longer – you just have to review it at the right times.

But, of course, that's easier said than done. How do you know what you're about to forget, and, therefore, what you should review? With traditional study methods, you basically don't. You can try to re-read a chapter a few days after you've read it the first time, or spend some time looking over old vocabulary as you're learning new. But there are two problems with this method. First, you end up playing a guessing game, trying to find the sweet spot between reviewing too early and too late. If you review too early, a good portion of the material you review will be stuff you already know perfectly well, and you'll be wasting your time. If you review too late, you'll have completely forgotten the more difficult material, and you'll have to relearn it. Secondly, even most committed students simply don't do it (and forget about people who aren't currently making learning their full-time job). It's time-consuming and difficult to prepare and stick to a plan for reviewing, it's discouraging to see how much you've forgotten, and it's less interesting to spend your study time reviewing than learning new information.

Instead, if you're like most students, you resort to extensive "cramming" before exams or other deadlines; if you don't want to make it sound like you've been slacking off during the semester, you might just call it "studying," but the process is basically the same. It's the process of relearning everything you've learned and then forgotten over the course of the semester, which turns out to be a large percentage of it – probably most of what you didn't build on later in the course (going back to the forgetting curve graph at the top of the page, if you learned something briefly from your textbook or a lecture at the beginning of the semester and then don't use it again, by the time finals roll around there's less than a 10% chance you still remember it). While cramming is not exactly pleasant, it usually gets you through the exam with an acceptable grade. But within a few days of the exam, you've already forgotten it again. What, then, was the point of studying all of that material? To pass the exam, of course, but what was the point of having an exam if it didn't actually test whether you were actually going to retain the information you learned?

(If you want a break to watch a YouTube video, the "Five-Minute University" comedy routine is a satire based on how little people actually remember after a college education.)

Studying before an exam is in no way bad; indeed, it would be foolish not to (unless you were really certain you knew the content). However, the study ought to be a time to look over and review what you learned before, to get you thinking about what might be on the test, and to fill in small gaps in your knowledge, rather than a time to frantically relearn a large chunk of the content of the course in a few hours. But of course, cramming is common because it's hard to avoid forgetting things when you don't even know when you should review.

But a spaced-repetition algorithm can tell when you're going to forget a piece of information (or more precisely, when there's a high chance that you're going to – the process of forgetting is quite random). For instance, Anki uses a spacing algorithm that generally aims at roughly the 90% mark: it schedules each piece of information for a time when it's statistically 90% certain that you'll still remember that information. (Raising the percentage much higher leads to diminishing returns, where you have to review far more often with only a small increase in the percentage of information you remember.) With the algorithm calculating the time you're likely to forget, you no longer have to worry about what you might be forgetting: you just sit down to study regularly and the algorithm tells you what you need to review.

Anki (and other similar spaced-repetition software) stores information in the form of flashcards, just like the kind you write on paper index cards and flip through. This is the most effective way to study with spaced repetition for two reasons. One, flashcards are a great example of active review, where you must think of the answer when prompted (the opposite is passive review, where you simply read or otherwise encounter the information). Active review leaves a much stronger impression in your memory and enables you to go longer without forgetting the information. Two, the scheduling algorithm works best when it's applied to only small pieces of information. This goes back to my example of re-reading a chapter to review it: with that method, you read a whole section or chapter, which will contain some information you know and some you don't; with flashcards, you place each concept you want to remember onto a separate index card, and once you've learned the content of a card you can place it aside and do not have to review it with the pile of cards you're still learning.

Most people use flashcards for lists of items they need to memorize, like vocabulary, numbers, formulas, and so on. But it's also possible – and very useful – to make flashcards that test any kind of conceptual information. This is the basis of the spaced-repetition method and Anki – take what you're learning, turn it into well-made flashcards (which takes some practice; see the "20 Rules" article under the "Learning More About Anki" section for some great tips), and, as the SuperMemo motto says, forget about forgetting it.

Here's how to get started.

Using Anki

You can download Anki for free from http://ankisrs.net. There are versions available for Windows, Mac OS, and Linux. Once you've set up the desktop computer version, there are other options too: you can study online from any computer or device with internet access using AnkiWeb, or download a mobile app for iOS or Android. All versions of Anki sync through the AnkiWeb synchronization service, so you can study on any device you like. (Note: While the desktop versions and AnkiWeb are free, the iOS app costs $25. While this may seem expensive for an app, if you choose to buy it, you're supporting the development of the desktop version and AnkiWeb (a full-time job for the developer, with most of the software then being released for free) and the server costs for the AnkiWeb sync service, as well as the development costs of the app.)

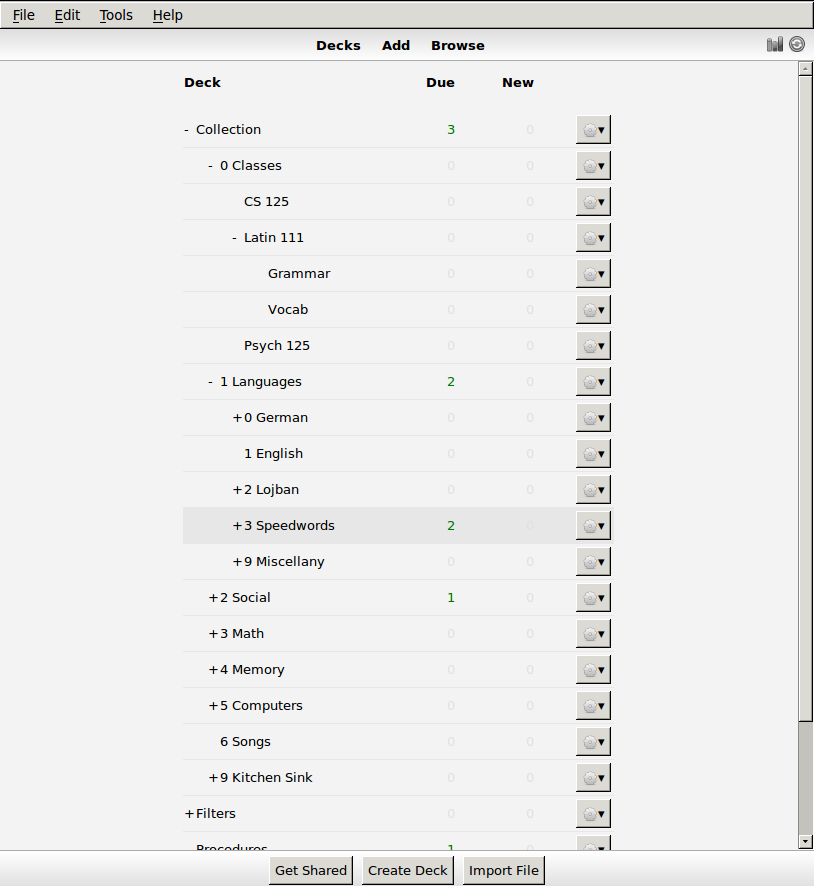

Here's what Anki looks like when I open it (if you've never used Anki before, you'll only have a single deck named Default):

[caption id="attachment_1170" align="alignnone" width="814" caption="Anki's deck list. You won't have a bunch of decks when you start."] [/caption]

[/caption]

The green numbers indicate cards that are due to be reviewed, and the blue numbers (there aren't any here, but they display in the right column) indicate new cards that you'll see today. I've already studied today in this screenshot, so there aren't many, but when I open it early in the morning, there's a cascade of green and blue numbers.

You can create your own flashcards with the "add" button or choose from a fairly extensive collection of decks contributed by other users by clicking the "get shared" button at the bottom of the screen.

When you go to review, you'll see the front side of a card. After thinking about the answer, you press the "show answer" button.

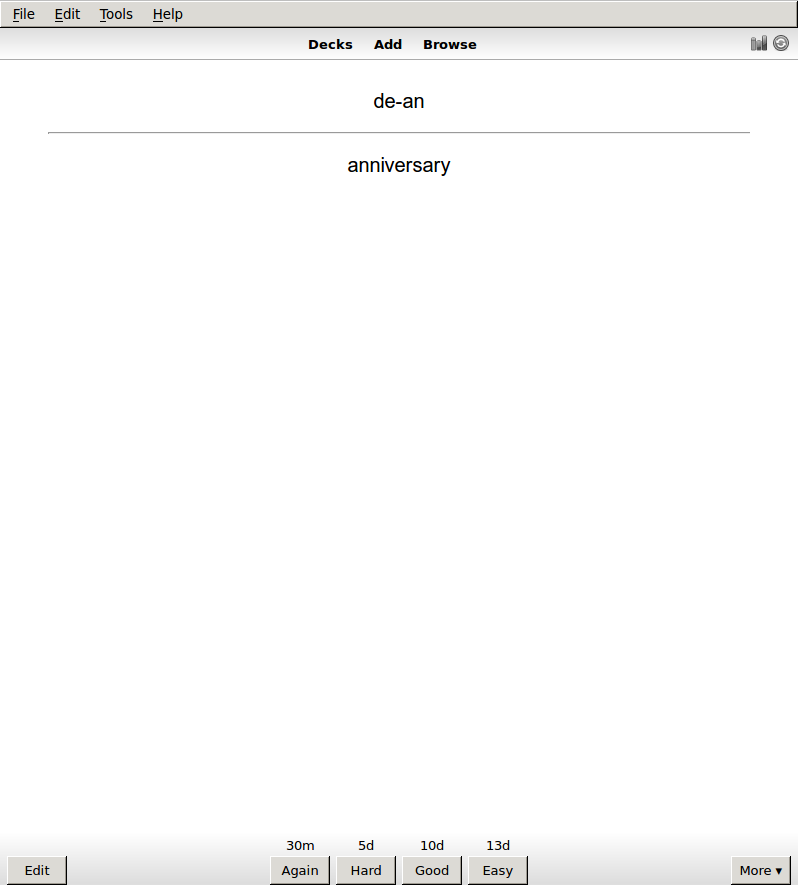

[caption id="attachment_1168" align="alignnone" width="798" caption="After displaying the answer."] [/caption]

[/caption]

At the bottom of the screen, there are four options. You select one of them (this is known as rating the card), based on how well you knew that information:

- Again indicates you forgot all or part of the content of the card or were otherwise unsatisfied with your answer. Anki will show you the card again in a few minutes (the default is 10; in this screenshot, I've customized the options and set it to 30).

- Hard indicates you were able to recall the answer, but only with difficulty. It shows you the card again relatively soon, but how soon depends on how long you last waited before seeing the card. If this is only the second time you've seen the card, you'll see it in just a couple of days, but if Anki waited a month in between presentations of this card, it will be a little more than a month before you see it again.

- Good indicates you were able to answer comfortably. Anki will wait somewhat longer than it would for a Hard rating before it shows you the card again. This is the default choice and the one you'll normally press the most.

- Easy indicates you felt the card was shown to you too early, before you really needed to review the information. Anki will not show you the card again for quite a while.

If you'd rather not click constantly as you review, you can use the 1, 2, 3, and 4 keys to activate the buttons and the spacebar to show the answer. The number above each rating button indicates how long it will be until you see the card again (in this screenshot, from left to right, 30 minutes, 5 days, 10 days, and 13 days). Not all options are always available due to different "modes" that cards can be in, like learning, review, and relearning. Don't worry about this for now; just pick an option that's offered and makes sense. If you click the wrong button, you can press Ctrl-Z or choose Edit -> Undo.

Many new users find rating cards to be difficult, as they've never done anything like it before. My best advice here is to just do your best to select an option and then not worry about it; while rating cards is important, it will all come out in the wash in the end, even if your study is not as efficient as it could be in the beginning. As you get used to studying with Anki, choosing a rating will become second nature.

Behind the scenes, Anki adjusts parameters with mysterious names like "interval," "ease," and "lapses," allowing it to schedule each card more accurately in the future and warn you when you're wasting too much time on one card. You don't need to understand how this works to make use of Anki, though; if you get into it and become interested in how it works, you can learn more about the algorithm.

Learning More About Anki

Anki has an extensive manual that covers almost every aspect of the program, as well as some introductory videos. Press Help somewhere in the program or browse to http://ankisrs.net/docs/manual.html.

If you have questions about using Anki, you can ask on the support site. Or you can email me if it's related to this Latin class in some way (see below, in Anki For This Class). Actually, either way, you'll be talking to me, because I'm a technical support rep on the help site.

If you get into creating cards based on your studies (which you totally should!), you should read the spaced-repetition-Bible article "20 Rules of Formulating Knowledge in Learning," which teaches you how to create flashcards that are easier to remember (and teach you the same information as ones that are difficult to remember). The difference between well-made cards and poor ones is astounding.

If you are interested in using Anki in this class, please send me an email (contact@sorenbjornstad.com)! I've got a small email list going, and if this is still going after a bit I'll create a Google Group or something for people to communicate. If you have questions, feel free to email me or catch me after class or lab.

Because I'm already making flashcards for this class, I will offer them for download as we progress through each chapter. I'll have the cards for a given chapter posted on or before the day we begin it.